The ambiguity between the real space-time and its representation is deliberately rendered in experimental mockumentary Those That, at a Distance, Resemble Each Other, which films with realistic austerity the process of crafting an exact replica of a custom-confiscated ivory tusk. With the camera aimed at the objects and the hands that manipulate them, the replica’s details and textures are an impeccable replication at high granularity, and even the original’s imperfections were copied perfectly on the replica. An object that hasn’t experienced a specific history has registered the marks left by that history. There is one scene where the original ivory and the replica undergo testing using some imaging technology that supposedly gives evidence of the age of an object. Here comes the anticlimactic, short, and barely noticeable detail – the technology reveals that the original, which the replica is modeled on, is tested to be a replica. The shot then jump cut to a different scene, leaving no language, no music, not even a contemplative pause for the perhaps most revelatory detail of the film, silently questioning the non-self-verifiable truthfulness of our world. Is there a distinction between the real and the counterfeit? Does that even matter?

The motif of the above-interpreted mockumentary echoes with Borges’ short fiction Circular Ruins, in which a wizard creates a young man through dreaming but in the end discovers through a fire that leaves him intact that he, too, is the dream projection of someone else. This is a fiction that discusses illusion, and even more so a piece that discusses the role of reality. Dream is the filter of reality, the projection of the psyche, and the transfer of consciousness, in which reality is replaced by illusion once a phenomenon is at odds with the “reality.” Since the Enlightenment, the world-system of the majority formed on the rational reality as the foundation. A phenomenon at contradiction with the rational reality is an illusion, and the way people reconcile with such contradictions is to render the phenomenon with representational lens (it is a dream, a hallucination, a tale) and reaffirm the singularity of rational reality. Once the phenomena at odds with people’s known truth is categorized as illusion in people’s mind, they can continue to live in consistency and coherence, like the wizard in the circular ruins before walking in fire unburnt.

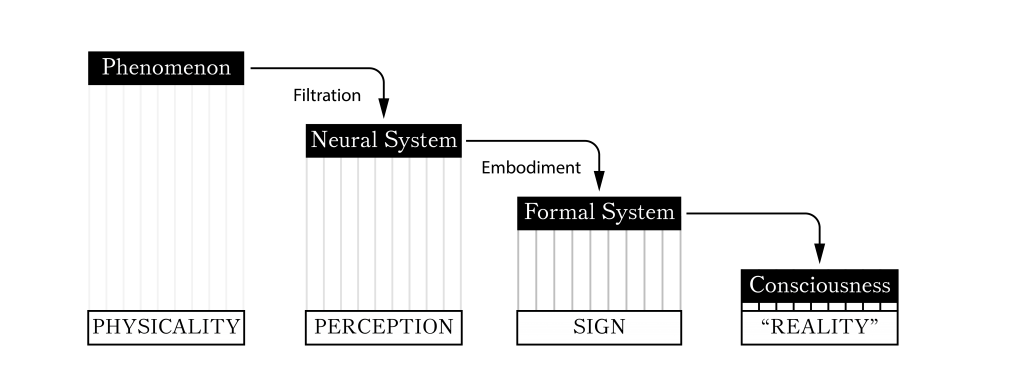

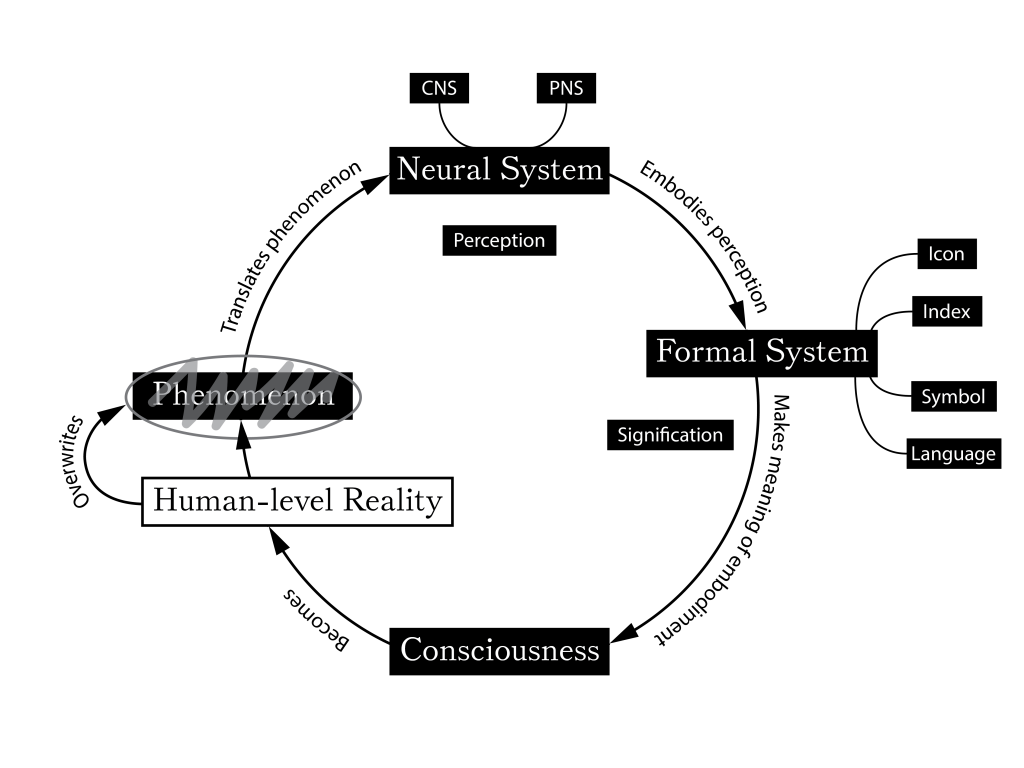

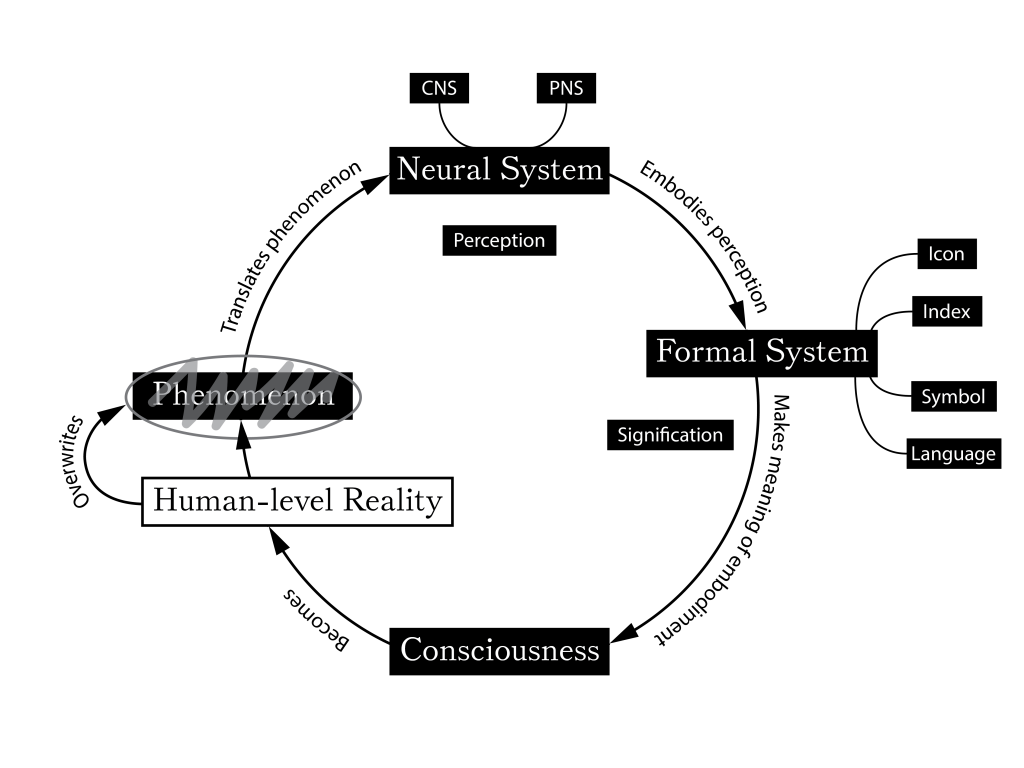

Profoundly influenced by the Enlightenment, our modernist culture makes us live in many self-evident, non-self-verifiable truths that together compose a reality. But traced to the root of humans’ epistemology, our cognition of the external world emanates completely from perception, from the sensory organs, translated through the neural system. Just as neuroscientist Christof Koch puts it, “the only way I know anything is because I feel.” When the conduit of reality, our neural system, make us disagree on phenomena, the foundation of rationality of reality is shaken. The downstream of reality’s conduit is the formal system of signs, of language, of a culturally constructed system of drawing meaning from chaos before phenomena enter consciousness. Because meaning is inevitably embodied and the sign is the means of embodiment, the foundation of an absolute reality now collapses. Reality is only relevant in the dynamic state. Imaged through the neural system and then embodied in the formal system, phenomenon becomes reality. What was once on the level of physicality is now transcribed to the human-level reality, as formulated by Edward Slingerland, which replaces phenomenon and becomes the reality that is more real to us than anything.

1. The Inversion of Reality-Illusion Transfer

Both Circular Ruins and Those That, at a Distance, Resemble Each Other tell the story in the order that what was once perceived as reality collapses and becomes illusion, but the relationship between phenomenon and reality is exactly the inversion of that – there is no a priori reality, and consciousness replaces phenomenon as the human-level reality. Religion and non-religious belief strive to shape our senses of reality as we seek for a unity. The epistemological trajectory of forming a reality is the reverse of the fictional account, starting from phenomenon, passing through and being altered by neural system, formal system and arriving at consciousness.

The legacy of religion that influences modern human beings regardless of their religious status is the introduction of the idea of soul, which is synonymous to self for atheists. For the human with a soul/self-consciousness, the world has many non-verifiable truths. One may believe that objects farther would be smaller than objects closer, just as Alberti perspective drawing and photography both testify, or believe that human rights are the fundamental and universal truth. But in both cases, the truths don’t exist in the physical world: Alberti’s perspective is premised on a PoV, which is a property of seeing, not a property of the object seen; human rights are a thought framework originating from the Euro-American West with a long history, contingent on the geographical and cultural context that relies on such a “contract” which regulates and restricts the hierarchical society. Perhaps to our distaste, all of these truths are more tied to the soul/self than physicality, but just as Edward Slingerland theorizes, these truths nevertheless feel indisputably true to us.

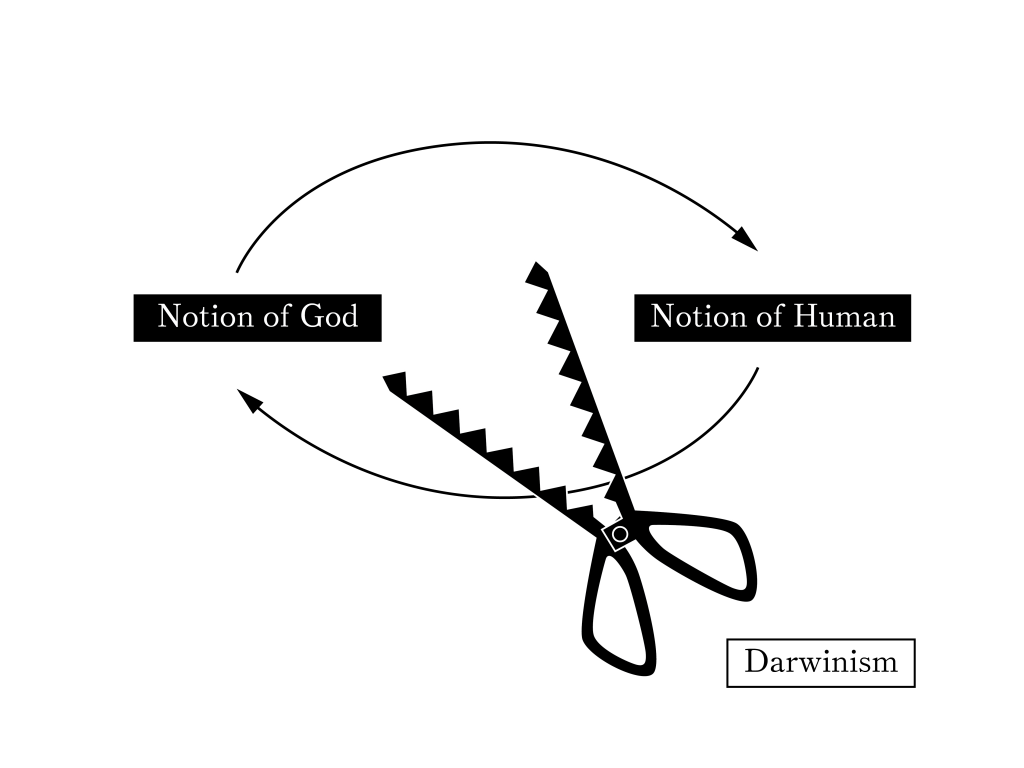

That is why Darwinism clashed so impactfully with the Christian society – not necessarily that Darwinism contradicts with the Creationist narrative, but primary because it shatters the Christian concept of the human being as the spirit of all life forms subordinate to only God. The evolutionists and Creationists do not debate over the origin of plants and animals – it is in the human realm where the schism manifests. Darwinism severs the biblical ties between the notion of God and the notion of human. It presents two contradictory realities, one in which humans are the active agent and subject under an omnipotent supernatural entity, and the other in which such subjecthood is diffused among all life forms. To a Creationist, that human is no different than animals is an illusion; to a Darwinist, the special condition of human as the sole subject of consciousness is an illusion. Neither is discussing pure physicality in this debate, just using physical evidence (ex. fossils and fabricated fossils) as tools of their respective argument of what reality is. In the constant, dynamic negotiation between the physical world and the self, the human-level reality is constructed and overtakes phenomenon.

2. Phenomenon Translated through Neural System: Perception

Phenomena first pass through senses of the neural system, which acts more like a selective filtration than a documentation. Filtered through the neural system, a phenomenon that contradict its physical properties impedes the absorption of the concept of reality as a unity. Used to describe such discrepancy, the word illusion originates from Latin root “illudere,” to mock, which sets a distance from the reality. Illusions are gaps between physicality and perceived realities. Auditory illusions are an example of humans’ limitation: the world you perceive is filtered. Bach as a classical composer addressed the gap in his creation of Ant Fugue, a musical experimentation of a series of repetitive rising tones that people perceive as one continuous tone rising into infinity. The listener does not perceive the frequency drop when several identical audio tracks overlap with a slight stagger. Cyclic repetition, as it passes through our neural system, becomes translated to linear infinity.

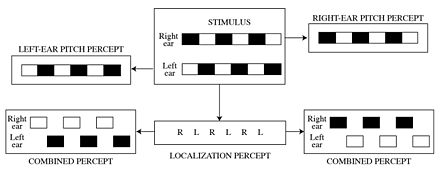

Like Bach’s Ant Fugue, there are numerous illusions happening at the neurological level. American psychologist Diana Deutsch devotes her career into a marathon research of all kinds of auditory illusions and their attributions. For instance, octave illusion describes the asymmetrical perception of soundtrack frequencies in the right and left ears, an effect that is mediated by right- or left-handedness. The most strange and riveting auditory illusion is the famous Yanny-Laurel experiment – a bi-syllabic sound that is heard as either “yanny” or “laurel”, dividing people into two groups who cannot hear what the other group hear. The trick is simple : people differ in their hearing range, and the soundtrack’s higher and lower frequency intervals alone sound different. These illusions show that humans’ epistemological channel is far from cognitive since perception can never be liberated from a selective filtration by the neural system.

Once the discrepancy in perception and physicality is empirically evidenced, it supersedes phenomenon and becomes termed “phenomenon” in the new context: we say that octave illusion is a phenomenon that the left ear and the right ear perceive different frequencies from a composite soundtrack that is played in both earphones. To call something a phenomenon implies a habit of keeping a distance from it. Phenomenon is a substance, a physical process, an object that is being framed by the gaze from the subject. Compared to perception and sign downstream, phenomenon pertains less to the psyche, therefore making less sense to the human-level reality. In drawing, phenomenon can be compared to parallel projection in which spatial relationships reflect properties of the object depicted, while perception can be likened to perspective in which objects are deducted from the viewer’s PoV. Once translated by sensory organs and neural system, phenomenon transitions into perception, moving closer to human’s subjecthood.

3. Perception is Embodied through Formal System: Sign

Humans do not ingest perception directly from the neural system – perception passes through a culturally constructed, implicit layer that treats it as a signifier, deciphers it according to rules and experience of the society inhabited, before it appears in consciousness. Our world is full of numerous signs, materially and immaterially, which mediates the experienced reality. One type of auditory illusion, named the McGurk Effect, shows the participant a video of an English-proficient person mouthing the word “far,” while playing the audio clip of “bar,” and vice versa. The listener would strongly bias toward hearing the word mouthed by the person in the video, as humans disproportionately rely on vision than other senses in negotiating with reality. The McGurk Effect’s scope of impact far exceeds octave illusion, scale illusion and Bach’s Ant Fugue in that the McGurk Effect extends beyond the laboratory setting into a common experience in the mundane world. With a non-anglicized name in an English-speaking country, I live intimately with auditory mishearing as my shadow. Every time I clearly articulate my name Yiou (pronounced as E-O), in an English-speaking environment, people likely hear Leo. I often receive a Starbucks coffee labeled Leo, and in the most extreme case, the Lyft car I called picked up a wrong person who declared that he was Leo, which was misheard by the driver as E.O. Where does that consonant “L” come from?

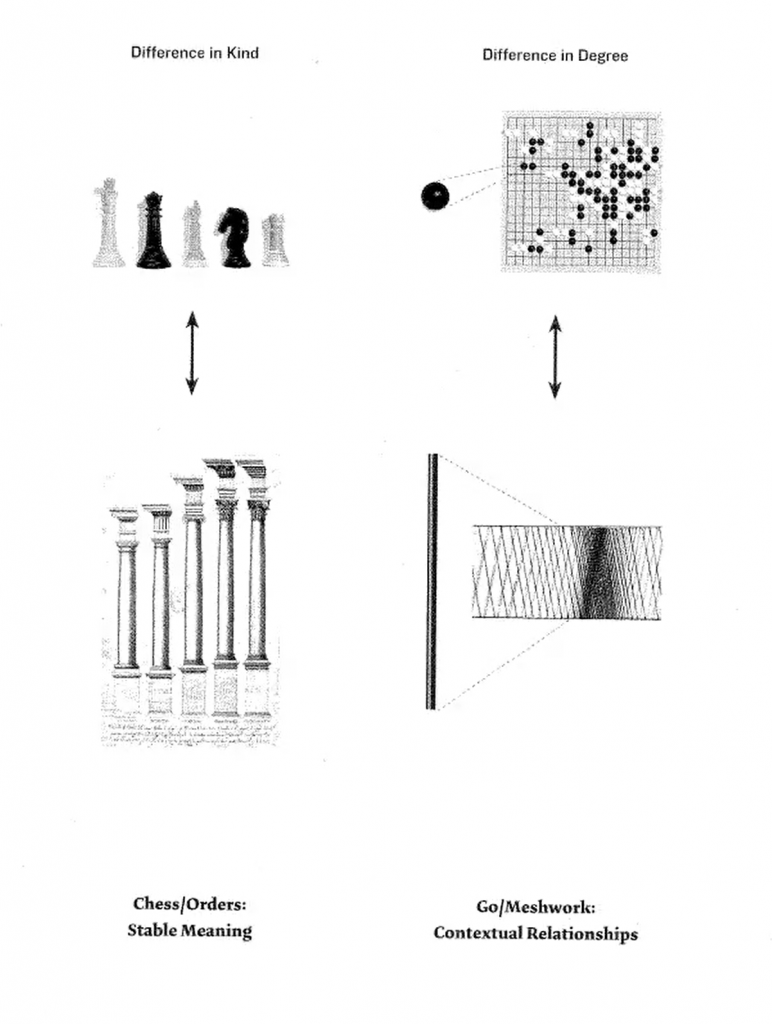

The daily ambiguity of our experience stems from the misalignment of formal systems. In every language, a set of vocabulary with fixed meanings are the “passive signs” as defined by Hofstadter, whose meanings are relatively stable, with “difference in kinds” as characterized by Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto. Leo in the English language is one of such stable-meaning signs, so are far and bar. The beginning consonant is not important when the listener can only make meaning out of the sensory stimulus by approximating it to a stable-meaning sign. Like an image of a geometry with a dent is perceived as the whole geometry with the viewer mentally completes the dent, people find it much easier to comprehend when the sound heard is mentally completed to be a word registered in their language. Embodiment of meaning among phenomena is like the process of searching for some small fishing boats in an extremely vast sea – people subconsciously latch on to passive signs before they consciously feel something makes sense.

When the addition of a sign changes the structural meaning and the sign acquires new meaning in relation to other signs, it is an “active sign” defined by Hofstadter, and its distinction from others is a “difference by degree” as characterized by Reiser and Umemoto, contextualized, playing a role in relation to other signs. The Chinese character, or the prefix and root in a Romanized language, is an example of the active sign because its heterogeneous meaning depends on what it is combined with. The game Baba is You by Arvi Teikari is an excellent simulation of a formal system of active signs. The blocks in this minimalist, nostalgic pixel game can be moved by the player and their functions can be redefined by the player, who not only behaves according to a set of rules but also changes the rules. The role of each block in Baba is You is an active sign that is embodied not only in kind but also in context.

Active signs and passive signs not only apply to abstract systems like language, but to all dimensions of our life, folding into a three-dimensional space that is immeasurable and infinite – the formal system is a system of signs, consisting of icons, indices, and symbols. Defined by Charles Sanders Peirce, an icon bears a factual resemblance to the signified, such as a yellow flame to fire; an index shares a logical correlation with the signified, such as the smell of smoke to fire; a symbol has neither a factual resemblance nor a logical correlation, but shares an arbitrary correlation with the signified, such as the English word fire to fire.

There is an even stranger case of embodiment, as the subjective detection of color is mediated by the native language one speaks. In English, and most of the Romanized languages, blue and green are two categories of colors adjacent on the color wheel, but in terms of wavelength (physicality), blue and green are a gradient on the light spectrum. The question is, where to draw the separation line to turn a continuous spectrum into two categorical colors? In many non-Romanized languages and archaic languages, the blue-green range of colors is termed singularly, or with breaks at different locations of the gradient. For instance, in Kannada, there is a word for blue/green and a word for dark blue/green; in this case, these two Kannada vocabulary cannot be translated into English with exact fidelity – in fact, they are usually translated into “blue” and “dark blue.” People who speak a language that colexifies (terms singularly) the blue-green spectrum can also see the difference between the bluest blue and green, they can also express the exact color they see with a specifier, such as yellowish. However, when the English-speaking person encounters the nuanced color on the range between blue and green, her formal system compels her to categorize it in her mind according to the color’s closeness to one of the signs. Perception is continuous but meaning embodiment is categorical. This is the gap between perception and consciousness: in the quest for meaning, we inevitably mentally distort physicality and draws phenomenon closer to subjecthood.

The relationship between perception and formal system is one between feeling and rationalization, the former is neurological reaction, and the latter is an arbitrary, artificial construct imposed by society. There is another large category of illusions that are not due to the neural level, but due to the signification level. Perception is like a hole in consciousness, and the brain will search exhaustively from its pre-existing repertoire of puzzle pieces for one puzzle piece to fit in the hole to complete it. This repertoire of differently shaped puzzle pieces is the formal system and each puzzle piece is a sign. The hole completed is the meaning.

The formal system is a system of myriad signs, not on paper but existing in a three-dimensional space. Phenomenon is filtered through neural system, and flushed through the formal system in a way similar to pouring a bucket of water into a three-dimensional field of drawers – most of the water is contained by the drawers, some drawers are empty, and some water that could not fill in the drawers spills over and evaporates.

4. The Constructed Reality: Alphabet-ness

In Burkina Faso, the French language dominates in schools and official institutions, partially because the country was recently liberated from colonization, and partially because the 59 tribal languages spoken in Burkina Faso long lacked a written language – a problem that shut Burkina Faso’s national identity from the third stage of culture, a symbolic culture as posited by Merlin Donald. Following Burkina Faso’s 1983 coup d’état, a nationwide campaign of literacy invented written language for the country, encoding the tribal languages with a European alphabet. This anti-colonialist language reform that borrowed the alphabet of the past colonizer provokes contradictory connotations, but the Burkinabé modernist creation marks an alignment of their language to a common sign system which, in this case, is a readymade alphabet. The alphabetization is not only a construction of a native language, but also the construction of the Burkinabé’s modern self. The self puts together a collection of non-empirically verifiable properties that stem from feeling, which is the fundamental paradox of consciousness – different from physicality, consciousness cannot be conceptualized or consolidated without an “alphabet,” either linguistic or non-linguistic.

The alphabet extends beyond its literal utility into a massive metaphor that people make sense of everything in signs of every means, formulated by Matthew Spellberg as “alphabet-ness.” Human-level reality is hinged on the familiar signs and rules of their own society as humans have an inward-looking tendency, a penchant to alphabetize our internal self, as well as alphabetize the external universe. An overactive formal system is accompanied by pareidolia, the overflowing false recognition of animated beings in objects, such as seeing a lion in the cloud or seeing faces almost everywhere: on a building façade, a sewer lid, or a pile of dirt. Pareidolia is caused by an overactive projection of alphabet-ness to the world of rich information and sensations. It may be meaningless in the practical sense in the modern society as it disregards physicality, but it is so inevitable and powerful that we cannot evade the feeling of moral extension to nonhuman and even nonlife substances. The human mind cannot help but extends our pain to empathize the pains of non-human animals, although we cannot access the phenomenological knowledge of whether animals feel pain in the same way we feel pain (scientific knowledge on the experience of pain is a different type of knowledge from the phenomenological knowledge – the direct, bodily experience of pain in the subjecthood of the other being); although modernity has long passed the mythical stage, the modern human mind still inevitably projects its own morality to land, life forms, and places as we fantasize about the “wrathful” storm and the “proud, black demon” of a storm petrel, the “abysmal” sea and the “safe” harbor.

But such single-directional fantasy, such pareidolia, and such overactive projection of our own alphabet to the world are not humans’ problem; in the contrary, this over-performing formal system is an utterly valid way to mediate the reality, real and meaningful to us humans. Despite the critique on alphabet-ness as the categorization of things for more convenient cognitive access, the visions of human-level reality feel true to us, are deeply believed by us, and actively facilitate economy, participate in society, help regulate human behavior, and maintain human conscientiousness. The projection of human pain to nonhuman animals activates strong ethos over that promotes animal welfare awareness and environmental protection; the extension of ethics to all lives, land, and natural phenomenon frames the modern relationship between human and nature; the projection of human values onto objects facilitates the ontological perspective on design.

The filtration of the neural system and the embodiment of the formal system are not reductive mechanisms as they may seem; these complexities work together to constitute the reality, which can be increasingly multiplistic.

5. Conclusion: Reality Overwrites Phenomenon: The Unity

To feel real, is not the synonym of to feel rational, but it is to make sense. A reality that makes sense to one is far more powerfully real than a reality that is empirically evidenced. At some point of our social life, most people are exposed to contradictions in realities, and begin to realize that your reality is not the same as my reality. Discrepancies are either caused by differences in how the phenomenon is processed by the neural system or due to subtle differences in the formal system that turns perception to embodiment of meaning. The way reality is constructed is characterized by an extended analogy of a conduit where the raw input, phenomenon, is filtered and translated by the neural system, and then embodied in the formal system, before arriving at consciousness, with each step enacting a little bit more meaning, and pulling physicality a bit closer to subjecthood. The resulting mental image is the reality.

The notion of passing through the conduit consisting of the neural and formal systems leads to the unity of phenomenon and reality. Once a pattern in perception or embodiment is discovered and a reality is formed behind consciousness, it is equated to the phenomenon as its replacement. For instance, before discovering the auditory illusion of Ant Fugue, we speak of Ant Fugue as an infinitely rising tone, while after understanding the illusory mechanism, we speak of the same thing as the phenomenon of perceiving an linear infinity in a cyclic repetition. People’s desire for a unity in phenomenon and reality and their distaste of paradox explain why reality will eventually overwrite phenomenon; they instinctively only accept one reality in their cognition. I term this tendency to let a single human-level reality dominate our life veritocracy. Veritocrats seek to unify physicality and reality, but only the reality constructed through the conduit of consciousness makes sense to them, so they replace the initial phenomenon with the human-level reality. The conduit is not linear but cyclic.

By shaping the reality, we also shape the way we inhabit the world. The conduit has limitations coming from the translation mechanism and embodiment mechanism – neural system and formal system. Consciousness needs a formal system to operate and even over-function to prevent people from falling into the Sisyphus trap – that is, the inability to feel and loss of motivation in an estranged world of utter meaninglessness. People can escape the fate of becoming Sisyphus because they find sense from the mediation of some symbolic system, no matter it is religion or other formal systems. Coming back to the question at the beginning: does it matter whether the ivory is true or fake when truthfulness is just a mind image? It is a question of value. From an ontological stance, it matters when the two ivory are compared in one context; from an epistemological stance, it does not matter as long as there is no way to tell. From a partially ontological, partially epistemological stance, reality is only relevant in the dynamic sense.