A concept and an object.

Concept

– Name: Otherness

– Origin and Brief Explication:

The origin of this concept is the essay “the Myth of the Other” by Zhang Longxi. The Other is created in a relative sense. It is the culture, nation or civilization different from which one identifies with. Foucault remarks observantly that one’s way of sensing and judging is so deeply rooted in the collective history to which one belongs that one ceases to be conscious of that. But he also states, in contradiction, that one enjoy art and music of many different cultures and historical periods with “equal preparedness for understanding.” However, if certain non-innate appreciative abilities are so deeply rooted in one’s cultural and historical upbringing, then one cannot possibly epistemologically treat different artifacts with the same readiness. Those phenomena that no one would question in a certain group in a certain period, those tacit puns that no one would hesitate to respond with a knowing laugh, may not be received with the same degree of understanding when presented to members of another group, because they don’t share the local, deeply wired, subconscious knowledge with them, and without information or immersive experience, may not know what to associate those phenomena or puns with. The epistemological preparedness is unequal — this is where Otherness manifests itself.

Object

– Name: A Digital Wunderkammer (Cabinet of Curiosities)

– Explanation:

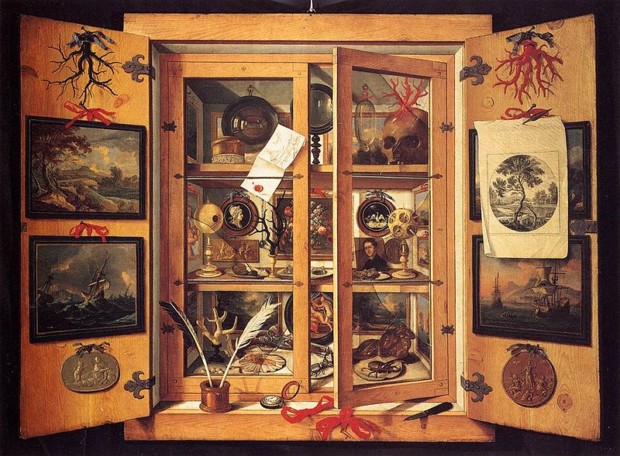

After the West and the East met, just as people are always curious about those far away places, different people, and various extremities, Renaissance bourgeoisie in Europe went through a frenzy of collecting specimens of flora and fauna from all over the world. Every upper-class family owned a “Cabinet of Curiosities,” as a way of collecting, archiving, and flaunting their curiosity for knowledge, desire for treasure, and vanity. But most of all, it is the early modern man’s attempt at probing Otherness, even by an object or a few, or just a scrap.

The Cabinet of Curiosities is an archive of Otherness. It sets up an angle, and mediates the relation between the looker and the looked, between the here and there, in which the cabinet as a piece of furniture becomes situated in the cultural zone of familiarity which the owner identifies with, and places the collection of objects in the cabinet somewhere that’s distant, as the looked. There ought to be a cabinet, as a symbol not only of ownership, but of distance. The Westerners hunted many exotic animals to extinction by the frenzy of the Cabinet of Curiosities, competing who was it to proudly claim the largest, longest, most beautiful or strangest creature in their Cabinet. Before animal protection and environmental awareness came to be, the Cabinet of Curiosities induced plenty of dark trades and vicious effects on ecology and colonialization. The Eighteenth Century’s enthusiasts for the Cabinet of Curiosities were unaware of the mediating effects of the Cabinet.

On my trip to and during my stay in the Domain of Unexpected Beneficence, I will also carry a “Cabinet of Curiosities,” but with the awareness of its mediation of Otherness. I want to bring with me a thing to collect, study, and commemorate the finds of the Domain and to document my own thoughts and emotions that arise from them, but due to the historical scar left by the Cabinet of Curiosities, I will only collect a digital picture, text, and model for each find. Therefore, I propose to include the Digital Cabinet in my carrier.

There are three types of people classified with regards to their ways to treating the Other. The first type of people worship the Other. Once they travel to a new land or place, see architecture and social customs that are different from what they identify with, they are as subsumed in awe as a pious connoisseur in Renaissance standing in front of the largest alligator skull in his friend’s Cabinet of Curiosities. These people tend to copy the elements of the Other, especially, as I am most concerned, in the way of architecture. The second type of people condescend upon the Other. They self-identify as coming from a more advanced civilization and dismiss the tangible and intangible culture of the Other as primitive and need to be enlightened. They tend to “offer help” to the Other. I, with my Digital Cabinet, am the third type that looks at the Other eye to eye, with respect, dignity, an open mind and intellectual curiosity. This intellectual curiosity is not material in that I do not desire to possess parts of the Other. All I need is a Digital Cabinet that would help me collect, document, and archive my finds in the form of digital images so that I stay clear of relics.

After all, the reason why I travel to the Domain of Unexpected Beneficence — similar to the reason why I travel at all — is to break the boundary between the Other and the Self. Too often we tend to accentuate our differences, as Borges formulates his view on Otherness, and I completely agree with Borges that we should venture into the Other, not because we want to possess the Other, but totally the opposite, because only through immersion in different peoples, cultures, and civilizations that we could gradually open up our provincial understanding, cease to indulge in our single-sided narratives of the Other, and desensitize ourselves from the shocks produced by the differences from our deep-rooted ways of appreciation.